The Sacred Art of Naming

Before we take our first steps or speak our first words, we are given our first root: our name.

In the Sikh faith, naming a child is akin to a spiritual blessing.

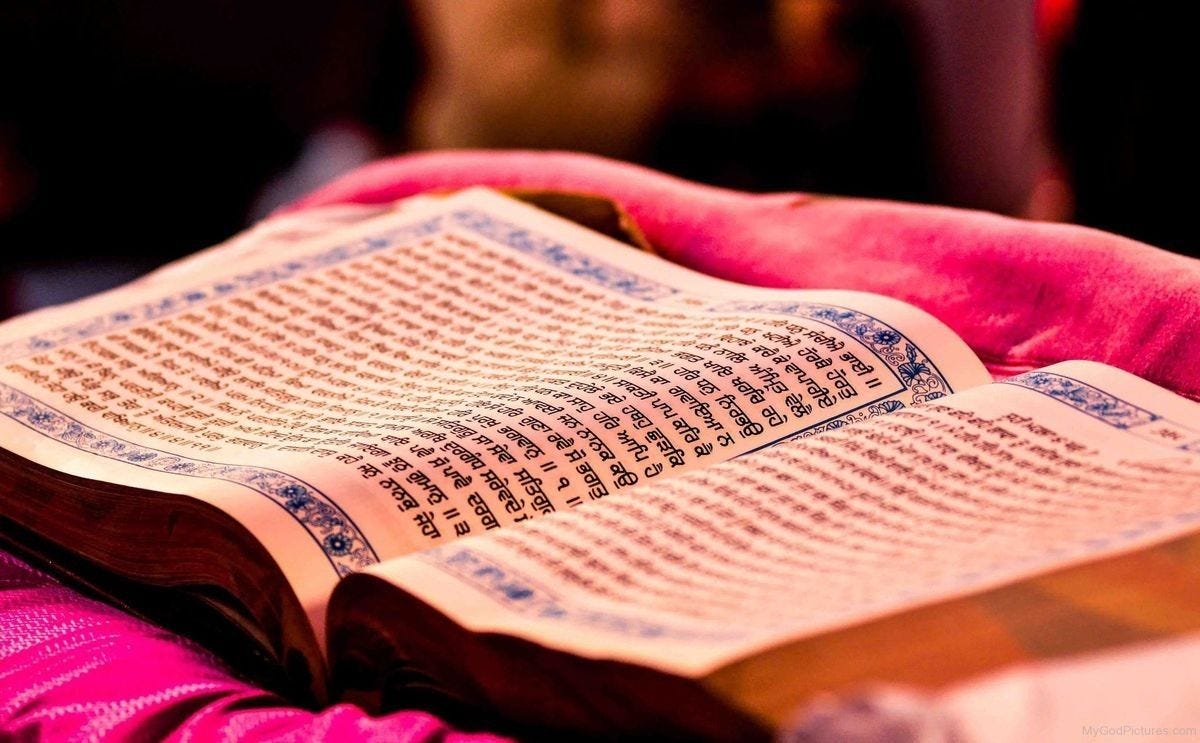

It unfolds in a ceremony known as Naam Karan, where the first letter of a child's name is revealed by opening the Guru Granth Sahib (Sacred Scriptures) to a random page. The first letter of the verse on that page becomes the first letter of the child's name.

Yet this tradition, like many others across the world, is fading at the edges.

Many Sikhs are opting out, choosing baby names in other ways. Perhaps before the baby is born, passed down from a grandparent, or they wait to understand the baby’s personality.

While I deeply respect individual autonomy, I can't help but yearn for people to safeguard this particular Sikh ceremony.

There's something transcendent about a name chosen through spiritual guidance, shaped by prayer, and imbued with meaning.

I want to preserve this way of doing things for future generations of Sikhs who might see the same. More on this below.

Preserving this practice isn't just about holding on to tradition for tradition’s sake.

When traditions disappear, we lose knowledge. And when knowledge is lost, we default to a homogenised world instead of one rooted in richness and diversity.

Why naming traditions matter

As globalisation and digitisation accelerate, the movement of people, ideas, and cultures is occurring faster than ever before. Once-distinct markers of identity are increasingly blurring.

Globalisation has its benefits. You can sip Colombian coffee in a London café, listen to K-pop in Nairobi, or find sushi bars in Mexico City. Cultures mix, influence each other, and adapt.

However, when we don’t allow for cultures to be distinct, we are just left with a sea of sameness.

Imagine a future world where everyone is called “X”, and you can't tell what stories, wisdom, or lived experience they bring to the table. That future is closer than we think.

When identity markers disappear, cultural appropriation thrives, and ignorance finds fertile ground.

Some might argue that highlighting our differences creates division, but research suggests otherwise.

Diversity breeds brilliance

Teams with varied cultural backgrounds and perspectives consistently outperform homogenous groups. They solve problems faster, think more creatively, and challenge stale ideas.

Our differences offer new ways of thinking, seeing, and being. And our names are one of the earliest signals to express you have something different to bring to the table.

If we are serious about preserving that power and resisting the slow fading of cultural identity, we must safeguard the traditions that hold it in place.

It starts with our names.

Names aren’t just sounds. They are blueprints, encoded with memory and meaning. For those of us in the diaspora, using our full names is a quiet act of defiance. A way of saying: “We exist, and we have something to offer too.”

History shows us what happens when we let traditions slip.

Across colonised nations, Indigenous names were stripped away, replaced with words designed to dominate and control. In immigrant communities, children are still encouraged to adopt easier names to blend in, as if carving away a piece of yourself is the price of acceptance. I wrote about my own experiences last week.

When we trade these traditions for convenience or conformity, we lose more than a name. We lose a cultural archive – a way of understanding the world that cannot be replaced.

If we truly value diversity, we must do more than acknowledge it. We must protect the rituals that sustain it. Naming ceremonies are acts of memory, turning a word into a vessel of history, identity, and belonging.

The Naam Karan Ceremony

In a Sikh household, once the mother and baby are well enough, the family gathers at the Gurdwara (place of worship) for the Naam Karan ceremony.

Devotional hymns are sung, expressing gratitude and joy – such as parmeshar dita bana (ang 628) and satguru sache dia bhej (ang 396) – a moment of thanksgiving to the Creator for the child's arrival.

This is followed by an Ardaas, the communal prayer seeking blessings for the child's health, happiness, and the welfare of every being.

The Guru Granth Sahib (Sacred Scripture) is respectfully opened on a random page, and the verse at the top left is read aloud. This verse, known as the Hukamnama (divine command), offers spiritual guidance and wisdom for the occasion or day. Traditionally, this practice is led by a Granthi, someone who serves as a custodian and reader of the scripture.

The first letter of the first word in this verse determines the initial of the child's name.

Traditionally, boys receive the surname Singh (literal meaning: lion) and girls Kaur (literal meaning: princess). Both titles symbolise sovereignty. These surnames emerged in 1699 when Guru Gobind Singh assigned them to all Sikhs to promote equality, reject caste hierarchies, and ensure women maintained independent identities.

The ceremony concludes with Anand Sahib (a hymn of joy), the sharing of Karah Parshad (a sweet offering symbolising divine blessings) and a communal meal known as Langar.

How I got my name

The Gurmukhi letter ਅ (aera) was revealed from the Hukamnama upon my first visit to the Gurdwara, and guided my parents in naming me 'Anoopreet.' My name is a blend of two words found in the Guru Granth Sahib:

ਅਨੂਪ (Anoop) means "incomparable," referencing the unparalleled nature of the Divine

ਪ੍ਰੀਤ (Preet) means "love" or deep affection, also referencing the Creator

Whilst there are a few ways to interpret, where I have personally landed is that 'Anoopreet' means 'Incomparable Love' and is my daily reminder to embody and express the same matchless compassion that holds us all.

Naming traditions from around the world

Writing this piece got me wondering about other cultures, traditions, and religions.

Naming ceremonies reveal our shared human desire to welcome children with intention, meaning, and connection to their lineage. I'm still learning about these traditions myself, so I welcome corrections and additional ceremonies I may have missed in the comments.

Rootkeepers is a space for us to honour our traditions. This living archive belongs to all of us.

Ghana (Akan People): Babies are traditionally named based on the day of the week they are born, with each "day name" carrying specific meanings. For example, a boy born on Saturday is named Kwame, symbolising leadership and strength, while a girl born on Monday is named Adwoa, representing peace and calmness. The naming ceremony, known as "Abadinto" among the Akans, typically occurs on the eighth day after birth. During this event, the father often selects the name, sometimes choosing to honour a beloved relative, with the hope that the child will emulate the virtues and qualities of their namesake.

Nigeria (Edo People): The "Izomo" ceremony takes place on the seventh day after birth. The eldest male family member leads prayers and breaks kola nuts, while the eldest female asks the mother seven times to name the child. After six symbolic refusals, the father whispers the chosen name to his wife, who announces it publicly. Symbolic items like honey, palm oil and coconut are used, each representing blessings for the child's future.

Nigeria (Yoruba People): The "Isomoloruko" ceremony occurs on the seventh day for girls and the eighth day for boys. Elders gather to bless the baby with names that reflect family history and aspirations. Names like Yetunde ("Mother has returned") honour ancestors, while Ayodele ("Joy has come home") symbolises new blessings. Water, honey and kola nuts are used to represent purity, sweetness and endurance.

Native American Traditions: Names carry deep spiritual significance, often reflecting nature, personal traits or visions received by elders. In Lakota tradition, children may receive a "birth name" and later earn a "spirit name" through dreams, deeds or rites of passage. Spirit names are considered sacred and must never be spoken casually.

Chinese Culture: Many newborns receive a "milk name" - a humble, temporary name believed to protect them from spirits. The formal name comes later, often reflecting poetic meanings or virtues. Chinese names place the family name first, emphasising lineage over individuality.

Japanese Culture: Names are chosen for their kanji (characters), each symbol holding distinct meaning. Parents select characters representing virtues like wisdom, courage or beauty, blending phonetic harmony with symbolic depth. The process of selecting kanji is often guided by numerology (kosei), believed to influence the child’s fate.

Persian Culture: Names often draw from poetry, mythology or religion, reflecting cherished virtues. Names like Shirin ("sweet") and Rostam (a legendary hero) connect children to powerful cultural narratives.

Islamic Traditions: During the Aqiqah ceremony, held on the seventh day after birth, the baby's head is shaved as a symbol of purification. Parents donate silver equal to the hair’s weight and choose a meaningful name, often reflecting Allah's attributes or significant Islamic figures.

Hindu Traditions: The Namkaran ceremony typically occurs on the 11th or 12th day after birth. A priest whispers the chosen name into the baby's ear, marking their spiritual identity. Names often reference deities or divine qualities.

Sikh Traditions: The Naam Karan ceremony is held at a Gurdwara, where the Guru Granth Sahib is opened to a random page. The first letter of the verse known as the Hukamnama (divine command) guides the child's name. The ceremony concludes with prayers and a communal meal known as langar.

Sri Lankan Buddhist Traditions: A naming ceremony is often held on an auspicious day chosen by an astrologer. The astrologer may also prescribe specific syllables or sounds for good fortune. The name may reflect astrological guidance, family ties or spiritual significance.

Tamil Hindu Traditions: In the Thottil (cradle) ceremony, performed around the 12th day after birth, the baby is placed in a decorated cradle while family members sing songs and offer blessings, formally introducing the child's name. A kolam (a decorative floor design) may also be drawn to invite prosperity.

Jewish Traditions: Boys are named during the brit milah on the eighth day. Girls may be named in ceremonies like Simchat Bat or the Sephardi Zeved Habat, often held within the first month. Names frequently honour deceased relatives, preserving their memory across generations. Sephardi families often name children after living relatives to honour and bless them.

Catholic and Orthodox Traditions: Names are bestowed during baptism, symbolising purification and spiritual identity. They often honour saints or biblical figures.

Protestant Traditions: Naming customs are often flexible, though names reflecting virtues like Grace, Hope or Faith are common.

Ethiopian Orthodox Traditions: Names often reference God, Jesus or the Virgin Mary. The baptismal name may differ from the everyday name but carries special spiritual significance.

Latin American Traditions: Naming customs blend Indigenous, African and European influences. Children may receive multiple names - one tied to heritage, one to spirituality, and sometimes one chosen by parents. Godparents often play a key role in the process.

Jamaican Traditions: Naming ceremonies traditionally take place 10 to 12 days after birth. Names may honour family elders, commemorate key events or carry spiritual meanings tied to protection and guidance.

Irish Traditions: Children are often named after saints, Celtic mythology or family members, reinforcing spiritual and ancestral ties. Naming ceremonies may include blessings for protection and prosperity.

Italian Traditions: Children are often named after grandparents, with the firstborn son named after the paternal grandfather and the firstborn daughter after the paternal grandmother, reinforcing family bonds.

Polish Traditions: Names are often chosen to honour saints and align with the child's "name day" (imieniny), celebrated much like a birthday.

Spanish Traditions: Spanish naming customs often include two surnames - one from each parent - preserving both family lines. First names often reflect Catholic heritage.

Greek Orthodox Traditions: Children are frequently named after grandparents to honour family legacy, with names formally announced during baptism. The baptismal name is typically chosen from a saint who shares the child’s birth date.

Nordic Cultures: Traditional Viking-inspired names often reflect power, nature or protection. Modern practices continue to emphasise links to ancestry and natural elements.

Pacific Islander Traditions: In Samoan and Maori cultures, names often reflect genealogy, tribal connections or natural elements, serving as spiritual anchors to family and homeland. Some names also commemorate significant events surrounding the child's birth.

Filipino Traditions: Names often blend Spanish, Indigenous and Catholic influences. Children frequently receive multiple names, combining religious devotion with family connections.

Slavic Traditions: In Russian and related cultures, children receive a patronymic - a middle name derived from their father’s first name. For example, a child named Anna whose father is Mikhail would carry the middle name Mikhailovna, marking her lineage.

Peruvian Traditions: In some Andean communities, newborns are given a "naming drink" ceremony known as wasi q'aytu. During this ritual, elders gather to bless the baby, and the chosen name is announced. The occasion is often marked with Chicha, a traditional maize-based drink, symbolising community, abundance and joy. Names may honour ancestors, reference nature or reflect significant events.

Swahili Traditions: In Swahili culture, newborns receive a birth name, or jina la utotoni, chosen by an elder and often inspired by the child’s appearance. After up to 40 days, parents and paternal grandparents select the jina la ukubwani, or adult name, to reflect aspirations for the child's future.

Thank you for making it to the end

If there’s one thing I’d like you to leave with, it is this:

When we allow traditions to fade in favour of convenience or conformity, we contribute to the cultural homogenisation that diminishes our collective human experience. If we truly advocate for diversity, it cannot remain stagnant in the theory. We must practise it.

Perhaps, it starts with the safeguarding of naming ceremonies. For me, they transform a word into a bridge that can both dismantle prejudice and deepen our sense of belonging.

By safeguarding these naming rituals, we honour the wisdom of those who came before us and create space for future generations to stand rooted in that very wisdom – building a world where no one is asked to shrink, silence, or erase themselves to belong.

I'd love to hear about your relationship with your name…

Was there a ceremony in deciding your name?

Who named you, and why did they choose that particular name?

Do you know the meaning of your name?

How has your name shaped your sense of identity or belonging?

Have you ever changed your name or how you present it to others?

In reclamation,

—

Loved reading this. What a great piece to emphasis how many common threads bring us together in the world . Was thinking about the qs you ask at the bottom- thought I’d share my experiences.

My mum wanted to name me Sharanjit before my Naam Karan was done. We grew up with Babaji’s saroop at home in one of our rooms so it was extra special that my mum conducted the ceremony. When she sat to receive the humannama- Shh came up which was a win-win situation.

I went to quite a white secondary school with barely any Asians and was so insistent on being called Sharanjit from 11-18 and then Sharan just stuck!

Sharanjit meaning ‘victory through divine protection’ and it literally embodies my whole being- I’m forever thinking about how protected I feel by God. ❤️

How beautifully you've written, Anoopreet Di ! Your words about naming traditions and cultural ceremonies resonate deeply - they make us unique yet connect us all highlights the balance betweens individuality and unity . I wish we could sit together (for more time now )and discuss the many thoughtful ideas you've ... ... just like my name, Sahin, which means 'falcon' or 'one who flies high,' symbolizing uniqueness and royalty. My sister's name, Ekas, means 'solitariness' or 'oneness with the Creator.' Isn't it thoughtful of our parents and grandparents to give us such beautiful, meaningful names? That truly shapes our identities and connects us to our heritage 🤍